As data-driven or machine-learning weather prediction (MLWP) steadily matures and is incorporated into operational forecasting systems, it’s critical that we step back and ask an important question: are these models useful?

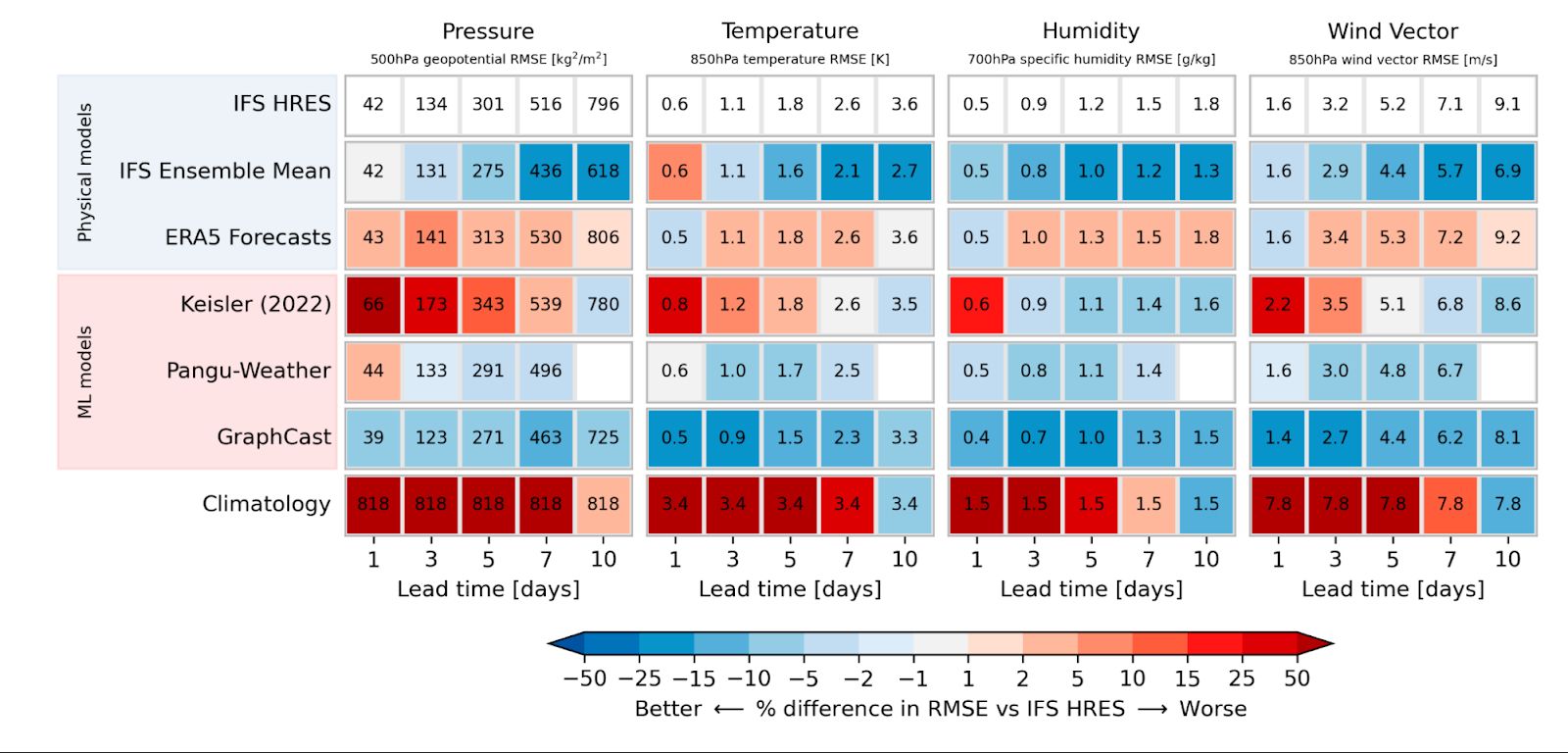

This question is subtly different from the typical one we might ask about how skillful these new forecast models are. Projects like Google’s WeatherBench and Microsoft’s WeatherReal tackle the skill question directly, pitting MLWP models against one another and state-of-the-art numerical weather prediction (NWP), comparing against surface stations or reanalysis. But this approach to measuring skill has a limitation: it boils down “skill” to simple, scalar metrics, averaged over many forecasts and large swaths of time and space.

As a meteorologist, I regularly use many different forecasting tools. Global, medium-range models like the ECMWF HRES or NOAA GFS; regional, high-resolution short-range models like the NOAA HRRR; ensemble models like the ECMWF ENS and NOAA GEFS, or their regional counterparts such as the NOAA/NSSL WoFS; or even statistical blends like NOAA’s National Blend of Models. Each model has its own strengths and weaknesses, and part of contemporary meteorology is understanding how – and when – to use each one.

This is the crowded field into which MLWP models are emerging. We already have some very powerful forecasting tools at our disposal; what do MLWP models add into this equation?

Brightband is committing to democratizing access to AI weather forecasting tools. Part of this mission involves educating when and why you’d want to use these tools in the first place. In addition to providing new ways to evaluate the performance of these models (such as our ExtremeWeatherBench project), we want to promote a transparent discourse: what do these models excel at? What are their weaknesses? When do they complement existing NWP forecasts – and when are they better?

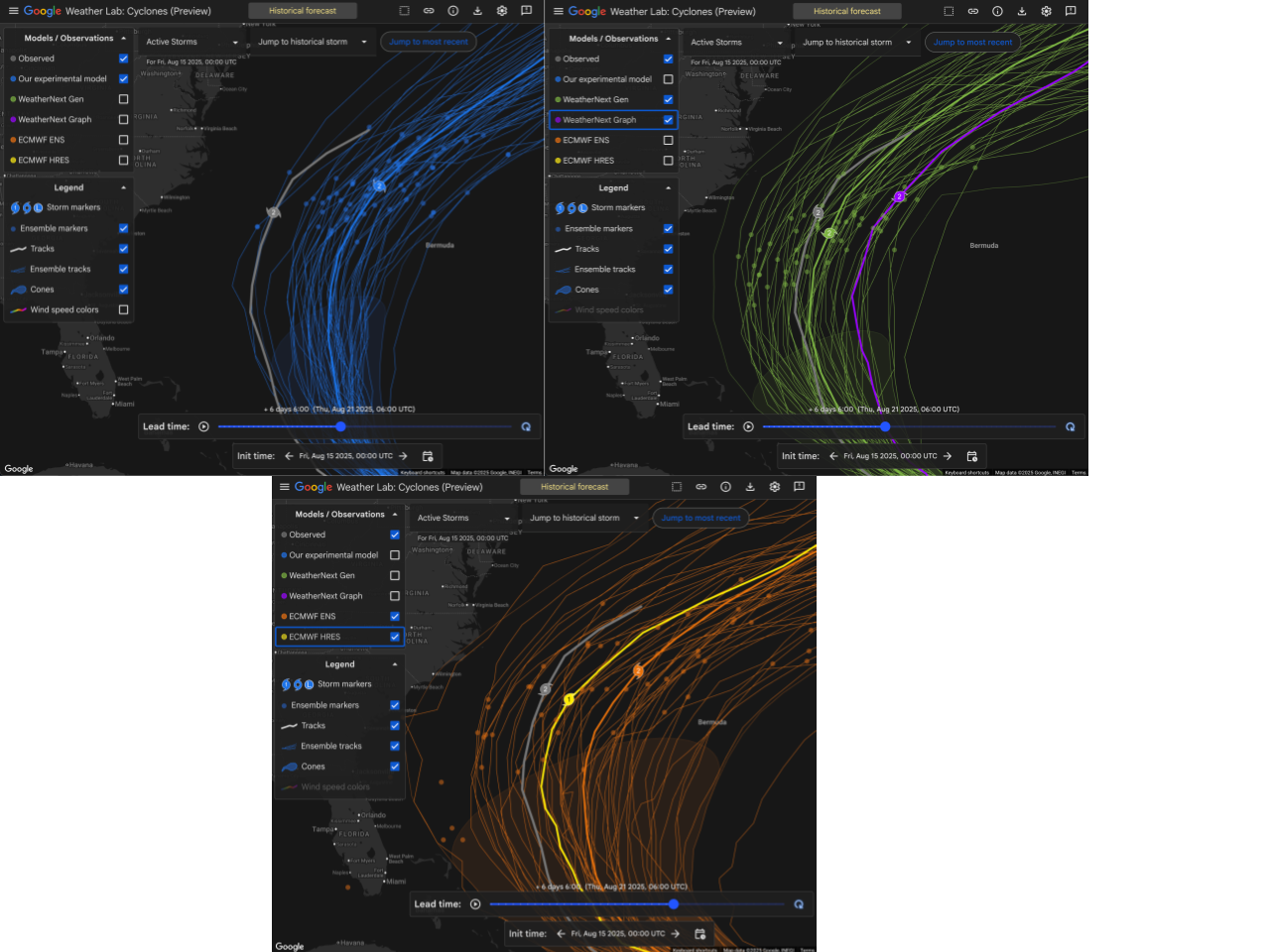

MLWP is part of a technological revolution that will change the way we understand and forecast the weather. The best way to usher in this revolution is to regularly use real forecasts from operational MLWP systems, and to compare and contrast them with forecasts from the NWP models with which we’re more familiar. Some efforts have already begun this work, including the 2024 NOAA Hazardous Weather Testbed – but much remains to be done in this space!

Moving forward, we’re excited to feature assessments of these models by expert meteorologists from across the weather community, in an effort to really understand these models’ performance in a real-world context. We’re starting by looking at tropical cyclones while the Atlantic season enters its most active period – but will continue with a wider variety of interesting weather from across the globe into the rest of the year. Our focus will be on any MLWP model that is currently run in production by a national modeling center or which is made publicly available online, and will include a set of models that Brightband runs operationally. If you’re interested in working with us on this initiative, please reach out at hello@brightband.com!

(hero image credit: CIRA/NOAA, space.com)